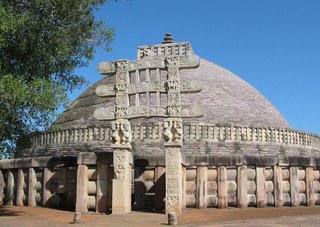

The Great Stupa at Sanchi, India. Sandstone, circa 50 BC to 50 AD.

Today I want to get into some Eastern art, because Eastern art is super cool. And while art history books might make you think otherwise, not all good things come from Greece and Italy. Like mandarin chicken. Or Gandhi. Or, uh, bird flu. Plenty of awesome things come from our Eastern brethren. Fireworks, Toyota, DDR... you get the picture. So today's featured work of art is the Great Stupa at Sanchi, India. Wait a minute, you say - aren't stupas Buddhist? Yup. Wait again, you say - aren't Indians, like, Hindus? Yes, you are correct again. (You're so smart.) According to Wikipedia (which may not be 100% reliable, but is 100% free) about 80% of Indians are Hindus. (Wiki also says that that's about 900 million people - that's about three times the population of the US. That's not really important to know, I just think it's kinda cool.) Less than 1% of the current population of India is Buddhist. Wait again, you say - what the crap is up with that? Well hold on and I'll tell you.

While India has almost always been predominantly Hindu, there was a period during which Buddhism flourished, thanks primarily to Ashoka, a powerful monarch who converted and built Buddhist monuments all across India to spread the religion. Ashoka lived from 304 to 232 BC, and it is during this time that the stupa at Sanchi was originally built. It was rebuilt between 50 BC and 50 AD, and made about two times larger than it had been previously. It's now about 120 feet in diameter, and 54 feet high.

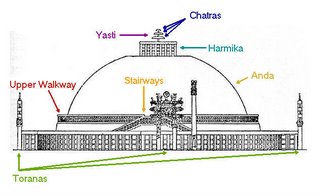

Let's talk a bit about stupas. As you can see, I've made you this fine diagram of the major parts of a typical stupa. (There are other, probably better diagrams available, but they're copyrighted, and not so colorful.) Stupas are essentially mandalas, or models of the universe. Now I'm not going to try to explain Buddhism to you, because I'm not nuts. I could write a book on Buddhism as big as the Oxford English Dictionary and still not fully explain it, so I'm just going to give you the basics you need to know to understand the Great Stupa. The main body of the stupa, or anda, represents the world mountain, which rises through the center of the Buddhist universe. The yasti, which rises through the top of the anda, symbolizes the axis mundi, the point at the center of the universe that connects heaven and Earth. The three stone disks on the yasti, called chhatraveli (or chatras for short) represent the three jewels of Buddhism: the Buddha (Siddhartha Gautama), the Dharma (the Law) and the Sangha (the monastic community). They're sometimes also called the Teacher, the Teaching and the Taught. (Pretend you're with me so far.) The yasti is surrounded by a small fence called the harmika. In Buddhist tradition, fences are used to gate off sacred areas. (That's why the entire stupa is surrounded by a fence.) The part of the stupa surrounded by the harmika is a square area that represents the domain of the gods. Finally, there are four gateways leading into the stupa called toranas, which are aligned with the cardinal directions.

Now this will sound funny, but you can't actually enter the stupa. The anda isn't hollow - there's no doorway leading inside. It's a solid mound of dirt, and contains relics of the Buddha, Siddhartha Gautama. Basically, you go through a torana and you've entered the stupa. Buddhists worship at the stupa by circumambulating it. Circumambulate is a fancy word for "go around in circles." Muslims do the same thing at the Kaaba in Mecca. So you enter the stupa and go around it in a clockwise direction. Then you go up the stairs and do the same thing on the upper walkway. By circumambulating, you follow the path of the sun, and become in harmony with the universe.

Back to the Great Stupa. Sanchi is most well-known for its toranas. The toranas provide the main instructional areas, because they are covered with carvings of religious scenes and tales of the Buddha. Unfortunately this next photo is of the back of a torana, so most of the figures are backwards, but you can see the volutes (the spiraly things) on the ends of each of the three architraves (the horizontaly things). That's because each architrave represents a scroll - you unroll the scroll and you see the pretty stories inside. A lot of them depict major events in the Buddha's life, while some depict what are called jataka tales, or events from the Buddha's previous lives. (Remember, Buddhists believe you are reincarnated until you reach Enlightenment.)

One final note about the Great Stupa - it is carved with the names of over 600 people who originally donated to its construction. One-third of those are women's names. That's just kinda cool. Go girl power.

I'm throwing in this last photo because it's really pretty, and it shows you what the land surrounding Sanchi looks like. Speaking of girl power, these photos were all taken by Eileen Delhi, another wonderful person who posted her photos on Flickr for people like me to use for free. You can see more of her photos here. Thanks Eileen, you rock.